Hyper monetisation of your attention, your time and off course your labor is a battle we have lost. However, the war to reclaim these lost areas of your life, of being a social animal and a human is still on. Gardening might seem like a humble act, and that is its biggest strength. There is no visible challenge that our national surveillance networks are optimised to catch.

Quiet rebellion, small wins, consolidation and building strength. One of my most loved and simple quotes is by Deng Xiaoping, former premier of China.

"Observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership." ~ Deng Xiaoping

The best people to learn from, identify and use weaknesses in the system and find little footholds to build on is to listen to your most competent enemies. The above quote comes from a leader of a nation, looking to reclaim the middle kingdom status of centuries past for his nation and his people while avoiding attention from opponents vastly superior and stronger. The current geopolitical scenario and China’s position in it highlight how much wisdom was held in his words.

Let's explore five powerful truths that reframe gardening not just as a hobby or lifestyle choice, but as a slow, radical resistance to the systems that seek to control our most basic needs:

5 Ways Gardening Becomes Resistance

1. Food is Freedom

"To grow your own food is to claim independence from a system that profits from your hunger."

Food is central to control, and those who understand history know this truth intimately. When governments rationed it, when corporations patented seeds, and when supply chains crumbled — communities everywhere instinctively turned to gardens. This isn't a coincidence; it's recognition of a fundamental truth about power and autonomy.

Consider the Victory Gardens during both World Wars. When citizens of the U.S, U.K., and Canada planted over 20 million gardens. These weren't just about reducing pressure on public food supply — they were about a generation experiencing, perhaps for the first time, what food independence actually felt like. Families discovered they could feed themselves without waiting for permission, without depending entirely on distant systems they couldn't control.

Even more striking is Cuba's response to the collapse of Soviet trade in the 1990s. Faced with severe food shortages, Cuban communities transformed rooftops, sidewalks, and abandoned lots into organic farms called "Organopónicos." This wasn't policy from above — it was survival from below, a mass pivot from industrial dependence to citizen-led agriculture that saved the nation from famine.

"Every home-grown tomato is a quiet revolution, every herb garden a small secession from corporate control."

When you grow food, you're not just eating fresh — you're participating in the oldest form of economic resistance. You're reducing your participation in systems that treat food as a commodity rather than a basic human need. You're discovering that the most radical act might be the simplest one: feeding yourself.

The beauty lies not just in the independence, but in the knowledge that builds with each season. You learn which varieties thrive in your specific conditions, how to save seeds, when to plant for continuous harvest. This knowledge can't be repossessed, inflated away, or disrupted by supply chain issues. It becomes part of you, increasing your resilience with every growing season.

2. Land is Power

"They enclosed the commons. We plant them back, one pot at a time."

Throughout history, access to land has determined freedom. In feudal Europe, landlessness meant serfdom. For enslaved Africans in the Americas, the promise of "forty acres and a mule" represented the difference between dependence and dignity. For colonized peasants across Asia and Africa, land redistribution movements weren't just about property — they were about the fundamental right to sustain oneself.

Today's landlessness is different but no less real. Most of us rent our homes, work in offices we don't own, and shop in stores that belong to distant corporations. But gardening offers a way to reclaim tiny territories of autonomy, even in the most controlled environments.

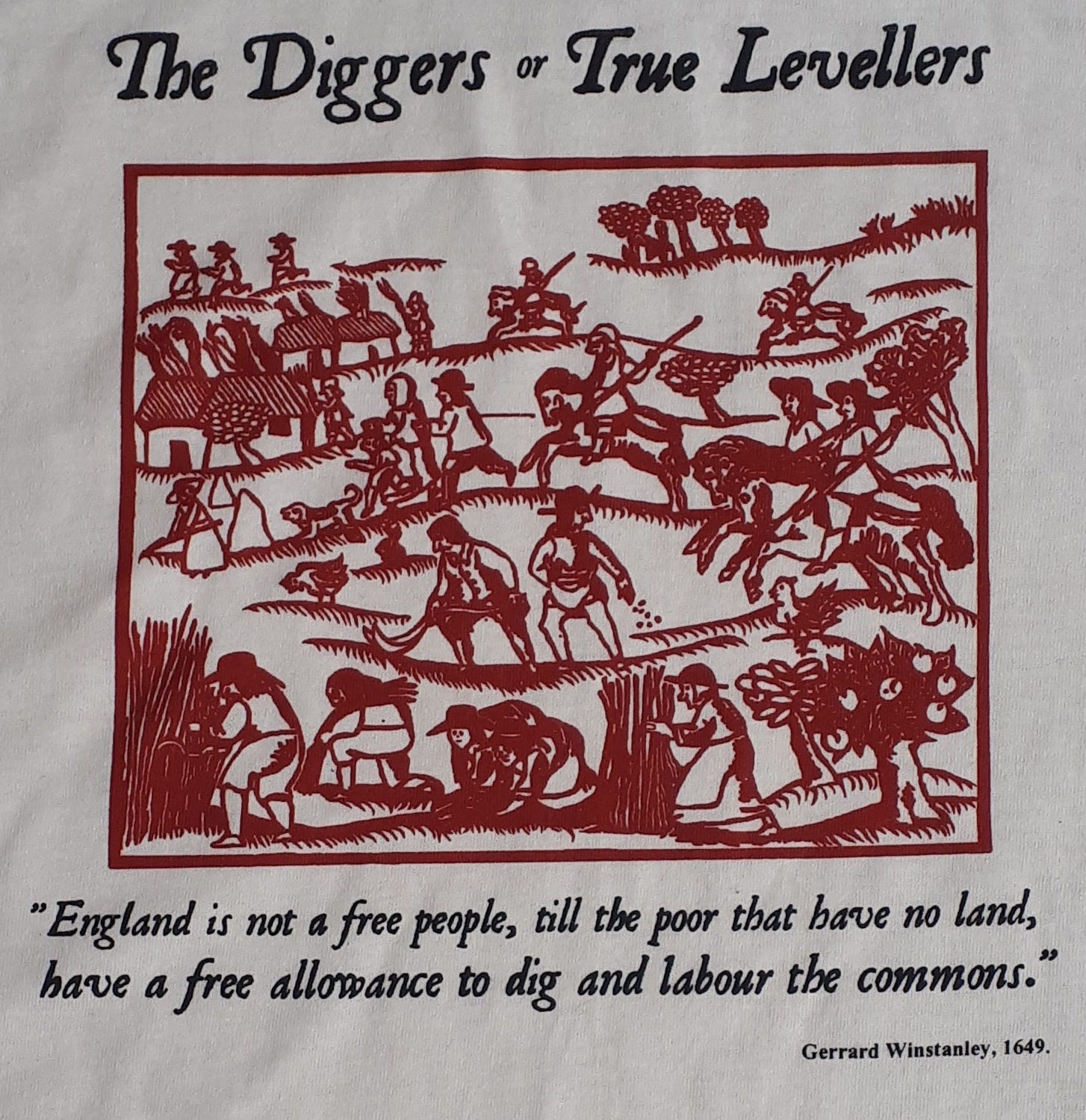

The Diggers of 1649 England understood this profoundly. This radical group squatted on common land to grow food, challenging both monarchy and private property with their shovels and seeds. Their leader, Gerrard Winstanley, declared that the earth should be "a common treasury for all." Though their settlements were eventually destroyed, their vision of land as a shared birthright rather than private commodity continues to inspire.

Similarly, Black Freedom Farmers in post-slavery America built independent food systems not just for economic survival, but to resist the sharecropping system designed to maintain dependence. Owning land meant owning your labor, your time, your future. It meant you could make decisions about what to grow, when to harvest, and how to live.

"Sovereignty isn't about owning acres — it's about owning your relationship with the earth that sustains you."

Even in a small apartment, when you decide what grows on your windowsill, you're exercising a form of land use that no landlord can entirely control. You're demonstrating that productivity and beauty don't require permission. You're proving that even the smallest spaces can be transformed into sources of abundance rather than mere consumption.

This is why container gardening, balcony farms, and indoor growing systems represent something more significant than clever space-saving techniques. They're technologies of liberation, ways of asserting that you have a right to participate in the fundamental act of cultivation regardless of your access to traditional land ownership.

3. Culture is Grown, Not Bought

"We grow what our ancestors grew, not what marketing sell us."

Modern capitalism doesn't just sell us products — it sells us the story that everything valuable must be purchased, that convenience trumps connection, that efficiency matters more than meaning. Gardening quietly challenges this narrative by reconnecting us with practices that predate consumer culture, rituals that ground us in something deeper than market relationships.

When you save seeds from this year's tastiest tomatoes to plant next spring, you're participating in a practice that's sustained human communities for thousands of years. When you learn to preserve food through fermentation, drying, or canning, you're recovering skills that capitalism tried to make obsolete. When you grow medicinal herbs and learn their uses, you're reclaiming knowledge that pharmaceutical companies would prefer you forget.

Native American food sovereignty movements have powerfully demonstrated this cultural dimension of gardening. By reviving heirloom seeds and traditional planting techniques like the Three Sisters (corn, beans, and squash grown together), they're not just growing food — they're regenerating cultural practices that colonization attempted to destroy. Each ancient variety preserved is an act of resistance against the monoculture that threatens both biological and cultural diversity.

The Sarvodaya Movement in India, inspired by Gandhian ideals of village self-reliance, promoted local crops and traditional composting methods as alternatives to the dependency relationships created by industrial agriculture.

They understood that cultural autonomy and food autonomy are inseparable — that growing your own food in your own way is an assertion of cultural identity against homogenizing forces.

"In every forgotten herb you revive, in every traditional technique you learn, you're withdrawing your consent from cultural monoculture."

This cultural reclamation happens on the most personal level too. When you discover that your grandmother's variety of beans grows better in your garden than hybrid alternatives, when you learn to make medicine from plants rather than always turning to pharmacies, when you develop your own composting system adapted to your specific conditions — you're creating culture rather than just consuming it.

The industrial food system wants you to believe that growing food is difficult, time-consuming, and inefficient compared to shopping. But generations of human culture suggest otherwise. By gardening, you're not just growing plants — you're growing confidence in human solutions, in the wisdom of traditional practices, in your own capacity to care for yourself and others.

4. Cities Can Rebel

"Concrete didn't kill nature. We just forgot we could plant through the cracks."

Cities are often portrayed as the opposite of natural spaces — concrete jungles where authentic life has been paved over. But urban gardening reveals this as a false choice. It demonstrates that cities can be productive rather than just consumptive, that neighborhoods can be ecosystems, that even the most built environments can bloom with life when people decide to make it happen.

Detroit's transformation offers one of the most powerful examples of urban agricultural resistance. When industrial collapse left thousands of vacant lots, many expected the city to die and communities crumble. Instead, citizens began reclaiming abandoned spaces for food production. Today, Detroit has over 1,400 urban farms and gardens, not because of government planning, but because residents decided to feed themselves and connect with each other.

These aren't just individual gardens — they're networks of mutual aid that strengthen neighborhoods. Families share surplus produce, trade seeds, and teach each other growing techniques. Children who might never have seen food growing learn where meals actually come from. Elders pass on knowledge while staying active and connected to their communities.

The story of South Central Farm in Los Angeles reveals both the potential and the challenges of urban agriculture. For over a decade, this 14-acre plot in the heart of LA was one of the largest urban farms in the United States. Over 350 mostly immigrant families grew food, built community, and created a green oasis in a concrete desert. Though it was eventually bulldozed for development, the years it existed proved that cities could feed themselves if communities were allowed to organize their own spaces.

"Every rooftop garden is a vote for a different kind of city, every window box a petition for urban beauty."

Urban gardening challenges the fundamental assumptions about how cities should work. Instead of being purely spaces of consumption — places where people work but don't produce — gardens transform neighborhoods into productive landscapes. They prove that cities can be more than economic machines; they can be places where communities are built.

The ripple effects extend far beyond food production. Urban gardens reduce the heat island effect, manage stormwater, improve air quality, and create habitat for wildlife. They turn neighbors into collaborators, vacant lots into community assets, and food deserts into food forests. They demonstrate that environmental and social problems often have the same solution: people working together to care for their immediate surroundings.

Perhaps most importantly, urban gardening reveals that cities belong to their inhabitants, not just their planners. When communities transform neglected spaces into productive gardens, they're asserting their right to shape their environment rather than just adapt to it.

5. Ecology is Agency

"Composting is activism. Soil regeneration is revolution."

The dominant story of environmental crisis often leaves individuals feeling powerless — climate change is too big, pollution too widespread, destruction too systematic for personal action to matter. But gardening offers a different narrative: one where individual actions aggregate into meaningful change, where caring for small patches of earth contributes to planetary healing.

When you compost kitchen scraps, you're not just reducing waste — you're participating in the fundamental cycles that sustain life on earth. You're taking organic matter that would otherwise contribute to methane emissions in landfills and transforming it into soil that can sequester carbon, support biodiversity, and grow food. This isn't just environmentally beneficial; it's a form of direct action that makes you an active participant in ecological restoration rather than a passive observer of ecological destruction.

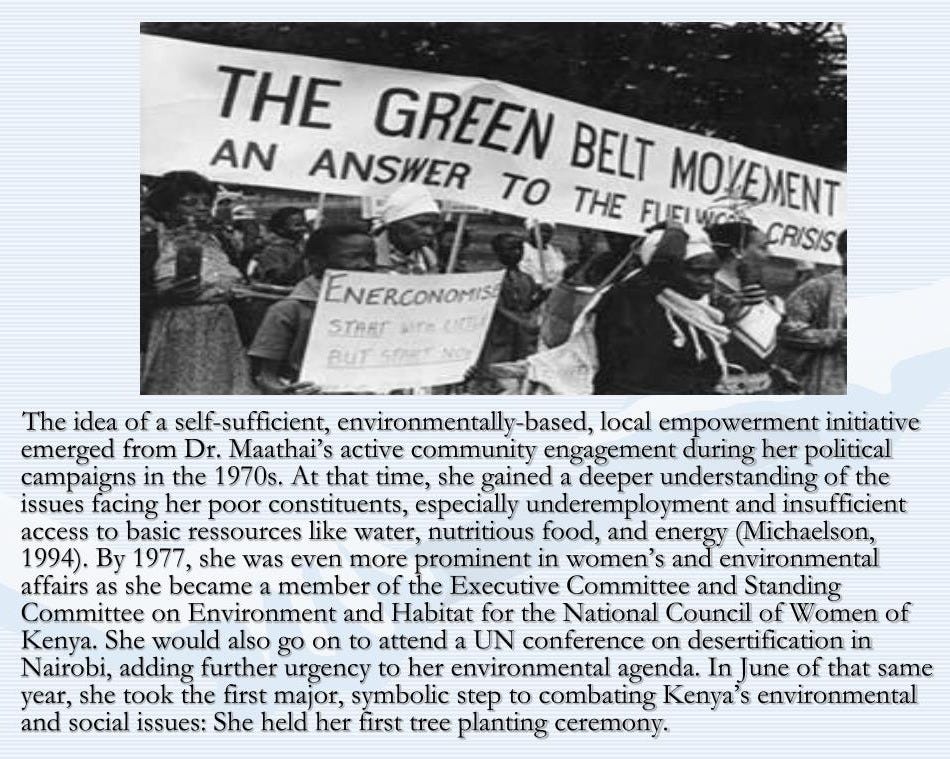

The Green Belt Movement in Kenya, led by Nobel laureate Wangari Maathai, demonstrated the political power of ecological action. Women planted over 30 million trees not just to fight deforestation, but to resist authoritarian governance and assert their right to care for their environment. They understood that ecological destruction and political oppression are connected — that environmental degradation is often a tool of control, and environmental restoration is therefore a form of resistance.

Permaculture movements worldwide have developed this insight into comprehensive design systems. From Australia to India, communities use permaculture principles to create closed-loop systems that waste nothing, produce abundance, and work with natural processes rather than against them. These aren't just gardening techniques — they're blueprints for decentralized, ecological ways of living that don't depend on extractive industries or centralized infrastructure.

"Every handful of healthy soil you create is a small victory against the systems that treat earth as a commodity rather than a community."

The act of gardening makes you responsible again — not just for consuming, but for creating. Not just for taking, but for giving back. You learn that soil isn't dirt but a living ecosystem, that plants aren't decorations but partners in the work of turning sunlight into life. You discover that you can be part of natural cycles rather than standing outside them.

This ecological engagement transforms how you understand your place in the world. Instead of seeing yourself as separate from nature — a consumer of natural resources — you become a participant in natural processes. Your garden becomes a place where you practice care, where you learn that human activity can enhance rather than degrade ecological systems.

The knowledge and skills you develop through ecological gardening extend far beyond your own space. You learn to read landscapes, to understand water cycles, to recognize healthy ecosystems. You develop what permaculture teachers call "ecological literacy" — the ability to see how natural systems work and how human activities can support rather than undermine their health.

Pause & Reflect

Take a moment to consider: Which of these five forms of resistance resonates most strongly with your own experience or aspirations? Where do you feel most ready to reclaim a little agency in your daily life?

Perhaps it's the simple satisfaction of eating a salad grown on your windowsill, knowing exactly where each leaf came from. Maybe it's the quiet pride of composting your kitchen scraps instead of sending them to a landfill. Or it could be the deeper recognition that learning to grow food is learning to be less dependent on systems you can't control.

"Resistance doesn't always look like protest. Sometimes it looks like planting."

The beautiful thing about gardening as resistance is that it benefits you regardless of its political implications. Even if you're not motivated by ideas about food sovereignty or ecological restoration, you still get fresh herbs, beautiful flowers, and the simple pleasure of watching things grow. The resistance is built into the act itself — every plant you grow is a small declaration of independence, every harvest a quiet celebration of self-reliance.

But for those who do see the deeper connections, gardening becomes a daily practice of hope. It's a way of betting on the future, of acting as if your individual choices matter, of demonstrating that another way of living is possible. In a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming, the garden offers a space where you can practice the changes you want to see in the world.

This is why we call it Anarchy Gardening — not because we're promoting chaos, but because we're celebrating the beautiful disorder of life growing wild, the gentle rebellion of seeds cracking concrete, the profound democracy of soil that feeds anyone willing to tend it.

"They expected us to scroll. We planted something instead."

Please share your thoughts, opinions and feedback in the comments.

Next, we will discuss Guerilla Gardening and start with some practical gardening skills

love this a lot, thank you for this reminder (just wish you didn't use AI images...)

I came in from the garden to cool off and read this. It's a total reflection of how I feel and think. And I think about this a lot.

I call it guerrilla gardening, but it's essentially the same thing, I think. I'm not an activist and only have a small plot, but I do save seeds from year to year and share them along with plant starts and produce to anyone interested. Hardly anyone is interested here. I'd like to try to change that, but age and physical abilities are tricky.

I think a lot about people living in cities and it's thrilling that they are reclaiming planting spaces.

I'm a huge fan of window sprouting. How else can you grow a quart of extremely high nutrient density food in about a week from seed to plate? A family could take care of an enormous portion of their nutritional needs by keeping several jars growing all the time. And they don't need land.

Also, a grow light, a few items and mason jars can get you set up for using the Kratky method of hydroponics in a tiny space indoors. It's not hard once you learn how. We grow what we call our basement salads" all winter. We grow lettuces and tiny tomatoes and sometimes herbs like basil or culinary celery. The lettuce grows better there than outside.